It started with a stove: Stories from Cambodia’s clean cooking shift

At the O'Dambang Muoy Health Centre in Battambang’s Sangkae district, Thursday mornings have become something more than routine. Around ten expectant mothers and their families gather weekly for guidance on nutrition, exercise, and pregnancy care. The space is calm, but the conversations are urgent.

“We used to only talk about the dangers of cigarette smoke,” reflects Mr. Tep Mony, a health staff member responsible for general consultation. “Now we talk about cooking smoke too, especially for pregnant women. It can cause shortness of breath, high blood pressure, and even lead to pre-term delivery.”

In Cambodia’s rural villages, cooking over firewood has long been part of daily life—familiar, comforting, and quietly hazardous. For generations, smoke from kitchens has gone unchallenged. But that is starting to change. Across health centres, homes, schools, and pagodas, a quiet shift is underway—bringing safer, cleaner ways of cooking into the heart of community life. The urgency is clear: Indoor air pollution from cooking with solid fuels is responsible for 3.2 million deaths annually, including over 237,000 deaths of children under five from pneumonia.

This expanded focus is no coincidence. Since 2024, the Smoke Free Village (SFV) initiative, implemented alongside and with support from partners Endev, Franke, and Lien Aid, has been supporting health workers, local authorities, schools, and communities across six districts to promote clean cooking solutions.

By integrating clean cooking into maternal health programmes, SFV has also sparked new conversations and action.

Mrs. Kim Sambath at O'Dambang Muoy Health Centre

Mrs. Kim Sambath, 42, for instance, is eight months pregnant with her fourth child. A former roadside food vendor, Sambath used to spend long hours inhaling smoke from her indoor firewood stove. “I constantly felt fatigued. When the health centre staff explained it was the smoke affecting me, I knew something had to change,” she says.

Her husband responded by purchasing an LPG stove and an electric rice cooker. “Now cooking is easier, my children help, and I feel safer,” she says. But she did not stop there. Sambath began sharing her experience with neighbours, encouraging other women to explore cleaner options. “It’s not just about my pregnancy,” she explains. “It’s about the health of my whole family, for years to come.”

Sambath’s voice joins many others in a growing chorus of change. In rural Cambodia, where nearly 80% of households still use solid fuels for cooking, smoke has long been considered part of daily life. But personal stories are now fuelling a different narrative.

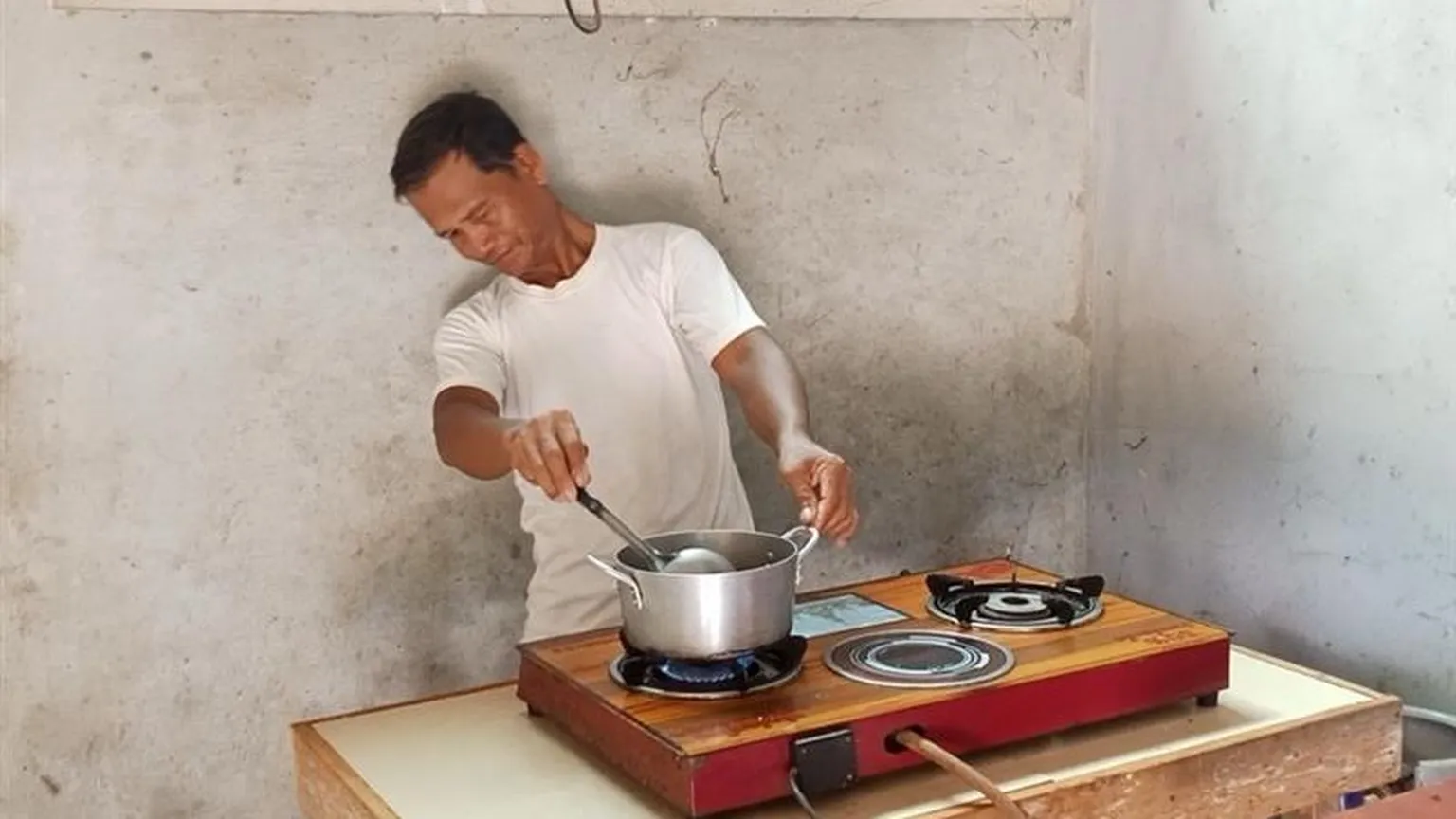

Mr. Prem Nee cooking on an LPG stove.

Mrs. Phok Seak using a rice cooker and gas stove.

In another province, Mr. Prem Nee, 55, and Mrs. Phok Seak, 64, both recall growing up around three-stone fires. “In 1995, we moved to a ceramic stove, but we still used firewood,” says Mr. Prem. “Engaged with SFV activities since 2023, I explored and understood the health risks. The cook fair was an important space to realise - it takes much longer to cook with firewood!”

He started small, first an electric kettle, then a rice cooker, and most recently, a large LPG stove. Mrs. Phok, meanwhile, began with a rice cooker and saved for months before buying a gas stove. “I’ve had eye irritation for years from the smoke,” she shares. “Now it’s easier to cook, and my health is better.”

Beyond convenience, these transitions are deeply personal, often hard-won, and increasingly collective. Both families have become vocal advocates, drawing from their own journeys to help others see the benefits of clean cooking. This blend of individual action and community connection drives the momentum behind SFV.

On the move for the visibility campaign.

Individual action and community connection

In the Basedth district, that momentum was recently taken to the roads, literally. Trucks adorned with banners and loudspeakers rumbled through six communes, bringing messages of clean cooking straight to people’s doorsteps. This mobile campaign wasn’t just about visibility; it was about inclusivity.

Each vehicle carried a team of community voices: local leaders, teachers, students, health workers, and even police officers. “We met people where they are, at home, in the rice fields,” says 70-year-old Mrs. Yin Sina, who decided to switch to clean cookstoves after hearing the messages. “Now, my kitchen is smoke-free, cleaner, and my family is healthier.”

Children played their part too. At Wat Kak Primary School, students performed songs advocating for clean cooking. “When students become advocates, they don’t just learn, they lead,” says Principal Mrs. Suos Khema. “They take the message home, and they make parents listen.”

From morning village meetings to twilight demonstrations, the campaign reached an estimated 11,000 people. For Mr. Kong Vong, Chief of the Basedth Health Centre, the signs of change are clear. “Families used to bring firewood stoves when staying with patients. Now they bring electric kettles. That’s progress.”

When clean cooking becomes a movement

Behind these visible shifts lie thoughtful design and targeted support. The SFV project recognises that behaviour change doesn’t happen in isolation. By training local authorities, health workers, and teachers, the project strengthens the ecosystem around each household, ensuring that clean cooking is not just introduced but embraced.

Crucially, the initiative also prioritises inclusivity. “We make sure to reach vulnerable groups, people with disabilities, women-led households, and low-income families,” explains Mr. Sum Sokhom, Basedth District Focal Point. “And in remote areas, we go door to door.”

As stories multiply from health centres in Battambang to cook fairs in Kampong Speu, the movement is growing, not just in numbers, but in confidence. Communities are no longer waiting for change; they are creating it, stove by stove, story by story.

While the smoke may be clearing from kitchens, what’s rising in its place is something far more powerful: a shared belief that better health, cleaner air, and safer homes are possible, and worth working for.